Category: Politics

PRIVSPLAINING

“If I said, “Boy, I really love corn dogs!” it doesn’t mean I actually love a corn dog. Because love has nothing to do with corn dogs. But it’s just language. It’s a state of mind. You take for granted that my intention is really to express that I enjoy them a lot and I want to eat one right now. That’s what it’s meant to do. But if you have an agenda and you want to take my sentence apart, you could certainly say, “Oh, my God! You love a corn dog? What do you mean by that? Do you want to marry it? Do you want to put it inside of you?” It’s like, “That’s not what I meant and you actually know that’s not what I meant and you’re only using it because you have an agenda so that you could get attention for whatever reason you have.”

We face daily pressure to behave according to gender, race and sexual norms, so it’s ironic that we use the same progressive values that aim to challenge these norms as a new standard of conformity.

In my pretty middle class, inner-city suburban existence, progressive values are mostly a given and something we strive to prove on a daily basis, not only as a personal aspiration but also for social credibility. It usually takes little to align this social-political algorithm, just the occasional Facebook post of a Ta-Nehisi Coates article or an Instagrammed Green Party ballot selfie every election.

Equally important is to avoid accusations of the opposite: racism, misogyny, classism, homophobia or transphobia, the recriminations of which are amplified in the digital age. As a result, personal ‘brand’ purity has become a dogmatic virtue. Our social media identities increasingly resemble political agendas, where our worth and effectiveness is measured by our ability to identify and call out marginalisation and privilege in face-to-face and online feeds. We’re easily wound-up and prone to react, with the onus always on the other, readily diagnose statements with ‘White, cisgendered straight male privilege’ – the predictive text judgement of these times – and respond to skepticism with privsplained logic akin to Hare Krishna or Scientologist street-bothering screed. Our focus has shifted from concrete political, legislative and social change to battles over academic and campus experiences. So dedicated to our new approach that proven allies who oppose our blanket judgements are criticised as enemies and the context of good satirical TV comedy is misinterpreted humourlessly.

These social media scraps against moral depravity is, in my view embarrassingly similar to those of the moral right – the same talkback callers, social conservatives and religious activists whose moral panic on welfare, sex and violence on TV, sacrilegious art and the role of certain musicians in social breakdown we snidely deride. Like them, we fear morally permissive values as driving bad behaviour and seek open confrontation to judge perceived transgressions. Like many born-again evangelists, there’s a tendency to blame others for preventing utopia. While certainly a combination of class, race, gender and sexuality reflect certain overall privileges or disadvantages, privilege, to me, is like meditation or prayer – a good exercise in self-reflection and contemplation of the state of the world. Yet, diagnosing others according to broad formulas that often rely on blanket assumptions simplifies complex individual human motivations and experiences and can easily misinterpret opinions and language without context.

Actions motivated by moral zealotry are always driven by political agendas. As social media users with the ability to play the role of moral arbiters in public, too frequently we act disproportionate to the situation and context to justify our political outlook and to accumulate gravitas as legitimate commentators – including those white, straight, middle class cisgendered males who appropriate others’ experiences. In a New Yorker article on this issue, the generational gap between an English lecturer at Oberlin College in Ohio and her students was noted: “Her generation, she said, protested against Tipper Gore for wanting to put warning labels on records. “My students want warning labels on class content, and I feel—I don’t even know how to articulate it,” she said. “Part of me feels that my leftist students are doing the right wing’s job for it.” Moral politics is ironically turning us into the very people we oppose.

Humanity chafes under moral conformity and history shows progress tending towards the blurring of gender, sexual and racial norms. Feminism, LGBTI and ethnic rights movements have made gains because they have rebelled against such conformity. Not only through protest but by developing concrete goals for bold political, legal, economic and cultural change, working with similarly-minded allies – many of whom they disagreed with on many issues – they have gradually won widespread public support.

Surely, genuine public belief in progressive ideals is more preferable, which depends on opposing moral panic of any political stripe. While real bigotry is inexcusable and should be challenged, not every perceived slight is worth a reaction nor every bigot merely the value of their transgression or their perceived privileges. Rather than replace one set of moral norms with social algorithm and forumla as another, real change must question all norms.

LABOUR CANDIDATES MUSTN’T DISMISS THE REBEL

It is claimed that the UK Labour establishment is in panic over opinion polls and endorsements indicating that left-wing leadership candidate Jeremy Corbyn is the frontrunner in the leadership election. Former leadership candidate Chuka Umunna has fronted criticism of Corbyn in an attempt to temper left-wing Labour members with realism, yet this might not be enough. Corbyn’s level of support arguably reflects a wider shift in centre-left values worldwide. In this environment, there are signs that primary voters are moving away from mainstream options in favour of their ideal candidates. Hillary Clinton’s strongest challenger in the Democratic primaries is independent, self-described socialist Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont, who is running on a left-wing platform similar to Corbyn, and is performing far better than anticipated. Both candidates are fuelled by grassroots campaigns with strong youth support. In that sense, Corbyn’s obvious parallel is Tony Benn’s close challenge to Labour deputy leader Dennis Healey in 1981.Corbyn and Sanders are, like McCarthy and Benn, transformed from rebels to serious contenders. Sanders’ campaign has similar vigour to Senator Eugene McCarthy’s campaign against President Lyndon Johnson in 1968, in which a narrow Johnson victory in the New Hampshire primary caused him to drop out. The outcome of these elections depends more on how their mainstream opponents respond to the new political environment.

So far, the Labour leadership election campaign has been lacklustre and often limited to the ad-nauseum repetition of words such as ‘aspiration‘ that have stripped of meaning to a degree that it wouldn’t be entirely surprise the public if the main candidates are either clones or alien replicants. Though Liz Kendall has arguably had more success articulating a coherent, down to earth narrative than other mainstream candidates Andy Burnham and Yvette Cooper, Corbyn has been the main beneficiary of this, probably because he has claimed the mantle of idealism. Corbyn acts as a Tony Benn-like figure representing a grassroots socialism and whose appeal contrasts with the image of professionally-designed, poll-driven, focus-group tested, policy and talking points communicated in pure political speak synonymous with the downside of New Labour. Likewise, Hillary Clinton is hindered by a long-entrenched image as an inauthentic, calculating politician in opposition to the curmudgeonly but passionate Sanders who has taken up the abandoned mantle of idealism which Obama had used to defeat her in 2008. In any case, what worked for Tony Blair in 1997 and Bill Clinton in 1992 might not succeed in 2015. In a world of austerity, ongoing inequality, mass data collection, drone strikes, and failed military interventions, there is an arguably greater passion for figures like Corbyn, Sanders, and others who articulate an passionate idealism rather than those who stake out calculated, strategic, tested positions. Candidates must acknowledge the limits of an overly cautious, professional approach.

The basic challenge of whoever wins is to achieve what Ed Miliband failed to do: channel empathy and articulate policies that make a meaningful difference in peoples lives in a way that captures an idealistic desire for change. For Burnham, Cooper, Kendall, or Clinton in America to win, this means communicating with authenticity and empathy rather than gimmicks and orthodox solutions. UK Labour MP Simon Danczuk cites Andy Burnham’s idea of more regional accents in shadow cabinet as a patronising, cosmetic solution that doesn’t address a deep distrust of politicians. Danczuk proposes that leadership candidates should listen, communicate authentically, and relinquish greater power to local government and service users for communities to find solutions to unemployment, poverty, and education that reflect their needs. This approach articulates both idealism for political change that is also pragmatically grounded.

If Burnham, Cooper, Kendall, Clinton or any centre-left politicians worldwide disagree with radical opponents, they would be better served with an authentic, pragmatic idealism rather than dismissal. If they cannot do this, then candidates like Corbyn and Sanders become – at least by default – the best candidates.

HIVE OF CARDS

Nicky Hager’s book Dirty Politics confirmed what many involved in politics already knew – that Cameron Slater is a garbage person with little compunction about undermining enemies in unethical ways – and alleges what people had suspected – that he was part of well-organised network of political staffers, affiliated bloggers, and sympathetic journalists intent on reinforcing a pro-National Party narrative. In my earlier post ‘Subcontracting Morality’, I argued that Cameron Slater was an adept blogger who understood both media motivations for popular, scandalous stories and knew how to leak information, with his history and connections as a political operator being crucial to his success. Hager alleges a far greater degree of unethical behaviour and coordination including the Prime Minister himself. Certainly, the blogging narrative of Slater, Kiwiblog’s David Farrar, and Matthew Hooton generally bears a striking resemblance to the core National Party narrative of a stable, moderate centre-right government led by a strong, likeable leader, in contrast with a divided left led by an unpopular, gaffe and scandal-prone leader despised by his own caucus and aided by the radical, beholden Internet Mana. It would be hardly surprising that there wasn’t been at least an informal cooperation between the Beehive, bloggers, and journalists – either ideologically sympathetic or those driven by profit demands who simply want a scoop – towards mutually beneficial outcomes.

As I argued in ‘Subcontracting Morality’, the media have essentially removed themselves from ethical debates on issues like private morality – like the Len Brown affair leaked by Slater – for the sake of profitable news. This indirectly empowers politically-connected bloggers like Slater to create/ leak/ release news rather than news organisations themselves, who can remain untainted from tabloid approaches while promoting Slater’s work. Allegations involving Key, if true, would indicate a similar approach to subcontracting amorality, where dirty tricks operations could be laundered through a third party – with Slater resembling something akin to a Cayman Islands money laundering operation. In this sense, it would indicate that the reach of professional political operations into social media and sympathetic journalism are deeper and more widespread than previously thought.

The fact that New Zealand’s most popular political blogs are those with political affiliations raises a question of the degree to which the public can trust information disseminated from these sources. In the latest stats from July, Slater’s Whale Oil was the most read blog followed by Farrar’s Kiwiblog. Third place was the Daily Blog edited by Martyn Bradbury, who wrote the Internet Party draft strategy, worked as a consultant for Mana, openly supported Cunliffe during the Labour leadership election, and backing IMP, Cunliffe, and a Labour-Green-IMP coalition to the hilt. In fourth place is the Standard, a collective of left-leaning bloggers with mainly pro-Labour sympathies, including prominent poster and Cunliffe confidant Greg Presland aka Mickey Savage. If Hager’s allegations are true, it would not be a significant stretch of the imagination for some cooperation and joint strategy among many on the left. The left simply hasn’t developed the breadth, depth, and strategic nous of Slater-Farrar-Hooton and journalistic allies, nor put aside egos and halted infighting as well as the right.

The political connections of these top four political blogs suggests a hypothesis that truly popular, influential political blogs with high readership may rely heavily on the access to insider political information and patronage from any political affiliations. This would be an alarming but not entirely surprising development that political interests have successfully entrenched themselves in the blogosphere while posing as nominally independent. Not so much reacting to or reporting the news but creating coordinated PR.

If the book is wrong, current trends in politics would indicate that greater informal networks between political organisations, bloggers, and media are inevitable. With a need for politicians to remain untainted, disavow ‘dirty tricks’, and call for people to #votepositive, there is huge incentive to engage in mutually beneficial relationships to promote an agenda.

OMNISHAMBLES

“Fleming’s fired the starting pistol, so we all can start firing our actual pistols into her fat, unelectable, smug head”

-Malcolm Tucker, The Thick of It, Series 4, Episode 4

Whether he is innocent or guilty, David Cunliffe has been tainted with the stench of the bipartisan practice of donations for access and/ or favours. Labour developed this approach during the 1980’s and 90’s, dominated it in the 2000’s, and National has perfected it. Labour cabinet connections to Liu look questionable, including Chris Carter‘s letter advising a fast tracking of Liu’s application in 2002, Rick Barker‘s dinners with Liu in China and possibly New Zealand around 2007-2008, and Minister of Immigration Damien O’Connor’s granting residency to Liu against official advice in 2004, and Liu’s $15,000 auction donation in 2007. Given Labour’s own practices on donations for access, Cunliffe has been tainted by association – despite the lack of clarity from Cunliffe’s letter.

While it could simply be the case of an enterprising journalist discovering Cunliffe’s alleged hypocrisy, this was more likely a leak coordinated between mutual political interests. Not only does this follow the hallmark of a setup – a politician set up to deny a premise that isn’t 100% true and a concluded narrative despite the vagueness of Cunliffe’s involvement – it’s election year, where Government is at stake and people will do most anything. If this is true, the aim was to destablise Cunliffe’s leadership so he must step down and be replaced obviously by Grant Robertson, 3 months out from the election.

WHALE OIL BEEHIVE HOOKED

“Nobody talks about fucking dodgy donors, okay, because it makes everybody look bad.”

-Malcolm Tucker, The Thick of It, Series 3, Episode 5

If this was a coordinated/ sanctioned move involving National-linked operators and the Beehive, then it was a gamble that changing leadership to relative unknown Robertson would make Labour more vulnerable and divided. There is even a loose link to Whale Oil on June 17th hinting of a forthcoming donations revelation in the Herald. However, a Cunliffe-led Labour could be just as ineffective during the election campaign as it has always been, which would be a positive for National. Also, Robertson – a former Beehive staffer and an excellent debater – could prove shrewder than Cunliffe and therefore a greater threat. Kiwiblog’s David Farrar has repeatedly asserted that he sees Robertson as future Prime Minister. Regardless, for National, it’s a case of symbolic comeuppance for gaining political capital in criticising it’s fundraising practices when both parties have a history of involvement.

ABC, IT’S EASY AS SILENT ‘T’

“I don’t know if you’ve seen those calendars that have got pictures of dogs that are dressed up and have got little dresses and hats on – she was turning my party into that.”

-Malcolm Tucker, The Thick of It, Series 4, Episode 6

If this revelation came from within Labour, it resembles the plot of the Thick of It, Armando Iannucci’s brilliant British political satire. A key plot in Series 4 is underperforming Leader of the Opposition Nicola Murray being taken down by her media advisor Malcolm Tucker through coaxing her to call for an inquiry over the suicide of a nurse over a policy she initially advocated in a forgotten email, resulting in the coronation of preferred successor Dan Miller. Farrar could be stirring the pot over caucus involvement, but it’s a possibility.

It’s well known that the ‘Anyone But Cunliffe’/ ABC faction of Labour hates him. During his leadership, Shane Jones was known for frequently contradicting Cunliffe publically, and Kelvin Davis, Chris Hipkins, and Phil Goff recently defied Cunliffe by speaking out against the Internet Mana Party. Yesterday, ABC-linked MPs avoided voicing support for Cunliffe. Given that rule that allows caucus to bypass membership and unions for a leadership election three months before an election comes into effect on Friday, it’s possible that this was a timed move to salvage what many see as certain defeat.

However, introducing Robertson to the public three months from an election is a huge challenge. If he were to accept the poisoned chalice, he’d risk being overthrown if he loses. If this is a Labour move, the situation resembles the 1990 general election where Geoffrey Palmer was overthrown just before the election by Mike Moore and Palmer’s deputy Helen Clark to lessen the scale of defeat. Yet unlike 1990, only a small increase in Labour support could allow a left coalition to gain enough support to form the Government.

Also against this theory is the potential damage to Labour’s image. If right wing pundits questioned Cunliffe’s legitimacy for having membership but not caucus backing during the leadership primary, the same can be applied for Robertson’s defeat by a wide margin in membership and union votes. To overthrow Cunliffe without a grassroots leadership contest could be construed as an undemocratic coup, which could result in a seething within party membership. The only justification would be if Cunliffe resigns and the caucus unanimously elects Robertson.

PUNDITS’ REACTION

The initial reactions on Twitter by pundits and bloggers on the left have been in favour of Cunliffe stepping down. This is likely more informed by a cognitive dissonance: a rush to judgement informed by desperation that blames Cunliffe and repeats the same mistake of last five years under Goff-Shearer-Cunliffe: blame the leader and anoint the next disposable saviour.

CONTEXT

Media reaction to Cunliffe’s dishonesty/ trivial mistake reflects a hypocrisy of media standards compared to, say, John Key’s donor transgressions, policy backtracks, and circumstances around Kim Dotcom’s arrest. But consider this: mainstream corporate journalists rarely question national security operations or fundamentals of economic order to any meaningful depth. But politicians being hypocrites is an easier sell that the public easily gets.

IT’S JUST A JUMP TO THE LEFT: THOUGHTS ON THE INTERNET MANA PARTY

“So come up to the lab and see what’s on the slab. I see you shiver with antici… pation.”

–Dr Frank N Furter, Rocky Horror Picture Show

Paddy’s Rort Retort

Patrick Gower accusation of “rort” at the Internet Mana Party alliance use of a Maori electorate to jump the 5% hurdle by a non-Maori party misses the point. A political alliance happened because of the unfairness of the 5% threshold, especially for new parties. Lowering the 5% or one electorate seat threshold was recommended by the MMP Review and rejected by the National Government, so parties operate accordingly within these flawed rules for advantage.

Yes, “The Maori seats are special. They have a unique constitutional role which is to give the Tangata Whenua a place of their own in the New Zealand Parliament”– but not so sacred as to be exempted from normal rules. IMP as a Pakeha-Maori alliance is not exceptionally different to the Labour-Ratana alliance of the 1930’s, NZ First in 1996, or the Mana Party as an alliance of Indigenous and left wing activists.

It’s Just a Jump to the Left

IMP’s potential success depends on public demand for a party to the left of Labour – something lacking since the defeat of the Laila Harre-led Alliance in 2002. Alliance members found new homes in Labour, the Greens, and Mana.

For years, space to the left of Labour was mainly occupied by the Greens, which once had a powerful working class focus most symbolically represented by Sue Bradford. The election of Russel Norman and Metiria Turei to the co-leadership has de-emphasised a socialist approach to poverty and focused more on broader green economics. With Labour, many former Alliance supporters would have compromised their values and experienced disenchanted with the Shearer/ Cunliffe/ Robertson as saviour/ villain sideshow. IMP’s election result will hinge on the ability to convince disenchanted Labour/ Greens activists and voters like myself who yearn for a more leftist choice but are unsure about the party.

A successful IMP is no threat to Labour or the Greens, instead a simple realignment of the left in an MMP world. If rumoured Greens fury at Harre’s defection is true, it would be a tribal claim to left voters like Labour MP Clare Curran’s similar attitude towards the Greens in 2011, which ignores the plural reality of MMP. In proportional electoral systems, especially in Europe, exists enough space for a social democratic party, a Green party, and a democratic socialist (in NZ allied with Indigenous left). National’s share of the party vote is aided insofar as the right wing realignment hasn’t happened yet and probably needs the death of ACT, NZ First, and the Conservatives to happen.

The reemergence of key Alliance figures Matt McCarten, Laila Harre, Pam Corkery, and potentially Willie Jackson across left parties is telling in terms of re-emphasis on the importance of grassroots mobilisation. Rather than a retro revivalcomeback tour, these figures possess institutional knowledge and campaign management skills crucial to the revival of the left overall and their parties must know this.

If IMP is successful, it won’t diminish the left vote but realign it and potentially turn out new voters.

One More Thing….

I raised concerns on an earlier post on this blogthat (1) IMP would be a contradictory coalition of ideologies akin to the Alliance and (2) the party would be dependent on personality rather than grassroots energy.

Harre’s appointment has complicated the first point, and though is more ideologically in-tune with Mana, she’s not known as a proponent of internet civil liberties. For IMP to truly develop legitimacy, the Internet Party would need prominent candidates well-versed in internet privacy, civil liberties, and youth engagement. If Harre focuses more on traditional left issues, the party will split. This proved difficult in the divided Alliance, so this would be a complex balancing act. To achieve this, Harre would need to combine left beliefs she’s known for with innovative new policies such as e-democracy through citizen participation in legislation and policy development to stake out a political space. This would mobilise a left wing base and could attract new voters.

On the second point, the development of a strong grassroots financially independent of Kim Dotcom’s finances would ensure long-term sustainability. Harre reduces concern over the power of Kim Dotcom, but the right will still raise the spectre of control held by a millionaire fighting extradition. IMP’s financial dependence on Dotcom in the long-term would reinforce a perception of the Internet Party akin to the Conservatives: a rich man’s plaything without roots. The Internet Party could justify initial investment only to build a grassroots membership and donor base and would have to do so within a parliamentary term – a big ask but crucial for long-term survival. The dominance of Jim Anderton’s leadership over grassroots activism killed the Alliance. Harre’s ability to learn from history will prove crucial to success or failure.

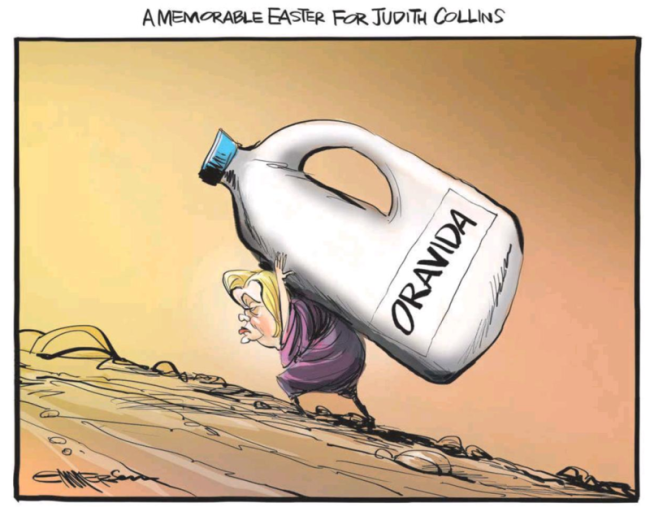

THE PRICE OF MILK

“For a quarter of a million pounds, that had better be one fucking hell of a dinner! If it’s not unicorn, you’d better be eating roast swan that’s been wrestled to death in a pit in front of you by the Queen herself.”

-John Oliver, on the ‘Downing Street Dinners’ scandal.

Both receiving conditional donations beforehand – like the donation-only anonymous dinners at Antoine’s Restaurant in Parnell or a Cabinet Club event – or after like with Oravida are two sides of the same coin. Both technically legal but raise significant ethical concerns over the role of money and access in politics.

The revelations over National Party practices are part of a global trend in political party funding networks. This week, Australian Treasurer Joe Hockey was revealed to be involved with the North Sydney Forum, a Hockey supporters network which includes a $22,000 per head special membership rate that includes private lunches and audiences with Hockey. The membership includes corporate board members, lobbyists, and long time Liberal Party donor/ operatives. This week, the Liberal Party is hosting a budget breakfast fundraiser in the Parliament building, to be attended by Tony Abbott and senior cabinet members for the price of $11,000 per head entry – just below the $12,000 limit for anonymous donors. This isn’t limited to the Liberals: the Labor Party in New South Wales has begun offering fundraising options between $5,000 to $15,000 to attend lunches, briefings and drinks with senior shadow cabinet ministers and leader Bill Shorten.

The worst case was in 2012, when the UK Conservative Party were revealed to have the Leaders Group program, where for £50,000, “Members are invited to join David Cameron and other senior figures from the Conservative Party at dinners, post-PMQ lunches, drinks receptions, election result events and important campaign launches.” The website also makes mention of other annual club memberships ranging from £2,000 local association networks and upwards.

These developments are rooted in the needs of modern political machines in a state of perpetual election campaign mode. A modern party is a professional one: head office staffers, external consultants and services including opinion polling, focus groups and advertising, events, and regional party organisations and networks. Not to mention the pressures of a political reporting approach more tailored towards ‘winners and losers’ and ‘who won the week.’ Political parties need to be at a war room footing to plan for the day, the week, and the next three years.

Despite that New Zealand parties are dependent on Parliamentary Services for the majority of their finances, perhaps we’ve passed the threshold of this balance being financially sustainable.

The needs of the political party machine and the media cycle incentivise political parties to actively pursue more and larger donations. Given that political party membership bases in Western democracies have fallen dramatically and insufficient to fund modern political machines, this means pursuing larger donors. Labour under Presidents Jim Anderton in the 1970’s and 80’s, Bob Harvey in the late 1990s, and Mike Williams in roles from chief fundraiser in the early 80’s to President under Helen Clark pioneered soliciting corporate donations. Williams especially acted a conduit between corporates and cabinet using more subtle methods such as arranging meetings between Clark cabinet ministers and then calling up for donations, as well as engaging corporates to communicate policy concerns to cabinet.

The events at Antoine’s Restaurant and existence of Cabinet Club reflect that National has institutionalised what Labour did informally. As a conservative party more open to a free market business model that implicitly and explicitly favours larger corporate interests, as well as being the incumbents, this has been a natural transition. National politicians could justify mutual interest between business and party philosophy, which is to an extent true. Yet given the financial weight of those donors representing corporates, those on corporate boards, or simply wealthy individuals, they would be more likely favoured over small business or regional business donors. This is likely to favour a free market environment dominated by monopoly and oligopoly corporate concerns: lower top income tax and corporate tax, less regulation especially on consumer regulation and the environment, and weak labour laws.

Consider the registered list of combined donations over $30,000 since January 2011, which certainly in favour of National, but with Labour also receiving corporate donors. National’s list is far larger, and containing notables including Bruce Plested of Mainfreight, the argriculture company Gallagher Group, Oravida, City Financial, Susan Chou (linked to Crafar Farms), and ‘Antoine’s Restaurant’ as the combined total of the infamous fundraising dinner. Labour has received little but since the 1980s has regularly received donations from corporates donating to both major parties.

The ethical question posed by the challenges to both National and Labour is the extent of influence private access can gain. This topic has been covered in an excellent NPR report for Planet Money, ‘Take the Money and Run for Office’, on the impact of money in American politics. From former Rep Barney Frank:

“People say, ‘Oh, it doesn’t have any effect on me,'” he says. “Well if that were the case, we’d be the only human beings in the history of the world who on a regular basis took significant amounts of money from perfect strangers and made sure that it had no effect on our behavior.”

Yet, Frank also says money isn’t evening, claiming “If the voters have a position, the voters will kick money’s rear end every time.”

To an extent, this is true: politicians claim strong personal principles and philosophy on politics and governance. But politicians are ultimately at the mercy of their parties for electorate selections, list rankings, so would tow the line if asked.

The NPR concludes that this type of fundraising is about access. According to the report, a least ¾ of all money fundraised is at breakfasts, lunches, dinners, and receptions, where access is paid and space for credit card numbers are commonly included on forms.

“Fundraisers and campaign contributions don’t buy votes, for the most part. But they buy access — they get contributors in the door to make their case in front of the lawmaker or his staff. And that can make all the difference.”

Certainly, New Zealand politics is not as dependent on lobbyist and third party money as America, but paid access to Government Ministers brings a candidness and direct influence is far beyond that of the ordinary citizen – even in a country where you can easily spot a cabinet minister in the supermarket. We don’t know what goes on, but the results of such financial benefits are obvious. Think Owen Glenn and Labour or the relationship between Maurice Williamson and Donghua Liu. Interestingly, Labour has the potential to gain power in this year’s election, and Oravida and Cabinet club allegations will no doubt play a significant part in this. But to gain and sustain power, they will need more fundraising revenue and there will be more willing donors open to an incumbent government. This isn’t simply a problem of one or two political parties, but one of the needs of professional political machines. The institutionalisation of privileged access reinforces the division between colluding elites and the public.

SHANE JONES WAS NEVER THE LAST STRAW

Certainly, Shane Jones’ retirement has Labour lose a talented politician. Half of the loss is that of an indigenous politician who could have made a significant contribution to Maori progress in a way not understood through the mainstream political lens (summarised well by Morgan Godfrey here and Carrie Stoddart-Smith here).

Yet, his departure also reinforces an entrenched narrative within media and political punditry of a narrow type of politicians who can attract working class voters who have been driven away from an out of touch Labour Party. Since the Clark defeat, there is a belief that Labour is dominated by “self serving unionists and a gaggle of gays”, with Jones as the last bastion of true no-nonsense ‘everyman’. While some aspects of this view are true, it’s a simplistic narrative driven by a professionalised political notion that working class voters will only vote for someone who appeals to those at the “RSAs, marae, pubs and to those browsing in Mitre 10 at the weekend.”

In this sense, Jones fits perfectly with this fetishised caricature of working class people in the sense that they can only be represented by domineering, salty, “red blooded males.” Indeed, media and political structures promote this idea of a “straight talker” as the only type who can speak for the people. In media, this is Paul Henry, Michael Laws, or formerly John Tamihere. In politics, this is exemplified by Shane Jones or Paula Bennett. People who don’t express positive opinions of those more different/ more disadvantaged than themselves but are “only telling it like it is”/ knowingly supporting our worst prejudices. Yet working class experiences are hardly subservient to or represented solely by that certain type of man. There are working class women – who are overrepresented in part time, waged professions – as well as GBLTI, Chinese, Indian, Pasifika, and others with diverse experiences and views. Reading over Labour MP profiles, Louisa Wall would certainly qualify as a representative of a diverse working class, but far more likely to be considered by the media and punditry as first and foremost a Maori and a lesbian.

Nor are working class males all boorish. New Zealand’s first Labour Government of 1935 to 1949 consisted almost entirely of working class people. PM Michael Joseph Savage, a former barrel washer at a brewery, and Deputy and successor Peter Fraser was a former dock worker. Both articulate, intelligent men who didn’t adhere to an antiquated idea of masculinity. Despite not having university educations that are the hallmark of modern politics, they developed a coherent, thoughtful alternative to austerity economics through public works and the establishment of the NZ welfare state. Likewise, Norman Kirk was a working class school dropout and more nuanced and visionary rather than boorish and divisive than, say, the accountant Robert Muldoon.

If Jones’ did have a genuine affection among working class New Zealanders, it came more from his ability to read and channel peoples’ daily concerns, most notably through his campaign against alleged tactics of Progressive Enterprises including price fixing and pressuring suppliers. Economic populism based on basic narrative that boils down economic concepts to something the public can understand is something the Labour Party has failed at for the last five years and could certainly use. If Jones’ departure is causing panic among Labour frontbenchers, it’s more of a reflection on Labour as dependent on one person rather than adopting an economic populist approach more widely. If Jones was the best they could do, surely it must be a reflection of public disengagement over a Labour Party consisting of too many cautious career politicians who don’t understand and/ or have the willingness to spend political capital challenging powerful economic structures that impact on peoples’ lives. If Labour cannot dent the popularity of John Key, using something like supermarkets as an example of economic inequality and unfair competition could force the National Party into defence mode.

The limit of Jones, despite his economic populist rhetoric, was that he didn’t provide a real challenge to the broad economic and social status quo. There was little discussion of alternatives to Progressive-Foodstuffs supermarket duopoly. Jones remained within the realm acceptability of mainstream media and pundits. If Duncan Garner, Guyon Espiner, David Farrar, and journalists from major papers were supportive or respectful with Jones, this more likely means Jones would have never substantially challenged core economic and social structures. Even his ‘maverick outbursts’ against international students should be considered cheeky fun not unlike that from fellow Northland politician Winston Peters: powerful rhetoric but unlikely to be acted upon once in power.

The fallout from Jones’ departure reflects the state of the Labour Party. Labour needs to convince people that it understands their concerns with both more populism and practical solutions that help people in their daily lives. This doesn’t need to come from a Shane Jones type. Clayton Cosgrove and Damien O’Connor as Jones’ replacements aren’t necessarily the answer. Remember it was former Minister of Communications David Cunliffe who broke up Telecom into two companies (phone and internet), which helped reduce the price of broadband internet. Cunliffe doesn’t need to go on the Nation and repeat the phrase “fair cop” to Paddy Gower to seem legitimate, because it isn’t. Cunliffe needs another Telecom. Like supermarkets.

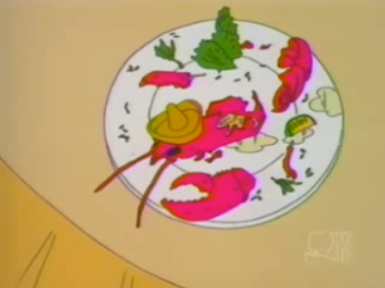

LOBSTER STUFFED WITH TACOS: MANA.COM AND THE STATE OF MMP

Moe: Hey! Hey! Sabu! I need another magnum of your best champagne here, huh. And bring us the finest food you got stuffed with the second finest.

Waiter: Excellent, sir. Lobster stuffed with tacos.

-The Simpsons, Dumbbell Indemnity

The potential merger/ alliance between the Mana Party and Kim Dotcom’s Internet Party is the equivalent of lobster stuffed with tacos or, depending on your political beliefs, a dead pigeon stuffed with rat feces then wrapped and deep fried in a Soviet flag as an unappetising political chimichanga. Simply put, it shouldn’t be. Mana is primarily an indigenous rights and socialist party, and the Internet Party is focused on civil libertarianism, internet freedom and supposed to appeal to younger, urban, National-leaning voters. The proposed deal has split Mana, with Sue Bradford threatening to leave, presumably followed by remaining socialists including John Minto.

Theoretically, Mana had the potential to be a Socialist-Indigenous MMP party but this action reveals it as an unequal partnership. Hone Harawira’s actions reflects the worst aspects of the left wing Alliance Party of Jim Anderton: a party of conflicted identity, driven by the whim of one person in an unequal partnership, and had Matt McCarten along for the ride.

‘Mana.com’ and many of the political choices and likely outcomes in the forthcoming general election reflect the deficiencies of MMP culture: personality driven, ideologically incoherent, and with unsustainable parties.

New Zealand’s political party system evolved similarly from British and European class-based ideologies and has maintained this path for most of modern history. All modern western politics is rooted in the Industrial Revolution. Three class-based ideological movements representing three class constituencies emerged during the late 19th century: working class social democracy representing the trade union movement; an upper class, conservative movement from industrialists, religion, and landowners; and middle class liberalism from educated professionals. From the Industrial Revolution until after World War One, Western political systems were typically dominated by conservatives and liberals. In New Zealand during the 1900s to the Great Depression, the party system was dominated by the Liberal Party which succeeded by the right-ish United Party, the rural conservative Reform Party, and a collection of small socialist parties that united as the Labour Party in 1916. When Labour won the 1935 General Election, the United and Reform parties, having already coalesced in government during the Great Depression, founded the conservative liberal National Party.

By the late 20th century, post-industrial movements such as environmentalism and anti-immigration have added to this theoretical mix, enabled by New Zealand’s adoption of MMP as a voting system. MMP inventors Germany or any typical western European proportional parliament would now include social democrats, conservatives, greens, and mostly but not exclusively democratic socialists, far-right/ anti-immigration populists, and classical liberal/ libertarians. In New Zealand, this extends to include Maori politics which, though historically dominated by Labour, contains a uniquely indigenous parliamentary politics.

Though the introduction of MMP has certainly diversified the political party system, New Zealand has not achieved such a vibrancy of sustainable ideologies like that of Germany or western Europe, largely due to factors unique to New Zealand.

Partially this is the result of political parties founded due to splits from Labour and National, ideological circumstances, and cross-ideological alliances of convenience. New Zealand First, founded as Winston Peters’ split from National in 1992, was a product of Muldoon and his protege Winston: social conservatism, populist state intervention, and, from my observations as a reporter for Select Committee News, a touch of the Rotarian in the form of curious, diligent MPs. It has also been reliant on Winston’s personality and initially a combination of Maori activism of the ‘Tight Five’ against more Pakeha conservatism.

The Alliance was rooted in New Labour’s split from the Labour by Rogernomics opponent Jim Anderton. The successor Alliance Party was an often contradictory coalition including New Labour Party, the Greens, the Maori Party forerunner Mana Motuhake, and the remnants of the former Social Credit Party, and was dominated by Anderton’s leadership and fell apart because of it. ACT similarly emerged as a consequence of Rogernomics, though in favour of further action, having been founded by Roger Douglas and included former Lange ministers and Rogernomes Richard Prebble and Ken Shirley.

The Maori Party emerged from Tariana Turia’s resignation from Labour but in fairness was built on a grassroots movement already developing before Turia’s split.

The United Party, the predecessor to United Future, was created as a coalition of Labour and National MPs as a party lacking any real demand for it and only having survived due to Peter Dunne’s hold on the Ohariu electorate. Ditto the former Christian Coalition, which was like a pleasant trifle at a church fete, albeit ruined by a layer of pedophillic sponge.

From the initial years of MMP, only the Green Party has emerged as a quintessential MMP party because it was borne out of a grassroots movement and has become an entrenched third party. The Maori Party and Mana would not count as MMP parties because they still rely on electorate seats. They have enough support base to become sustainable only if they unite, which is a huge challenge, hence Harawira’s preference for Mana.com. ACT, despite initially strong election results, political base, and politically competent MPs besides Prebble, it has relied on Epsom and won’t overcome this unless it achieves an ideological balance within and with the public. The Conservative Party is Colin Craig’s party: lacking ideology or strong public support, reliant on Craig’s financial largesse, and has spent more than Labour and more per voter than any other party in 2011. A less bombastic version of Clive Palmer without the dinosaurs and with monorail pods rather than Titanic II.

A recent opportunity to reform this system was the Constitutional Commission on MMP. The recommendations of lowering the party vote threshold from 5% to 4% and ending the one electorate seat exception for list seats could have potentially ended parties more reliant on leadership and electorate rather than ideological base.The National Government rejected these findings and opted for the electoral system to remain unchanged.

Conveniently, National’s electoral options remain positive. Initially, National contemplated the withdrawal of Murray McCully from East Coast Bays to support Colin Craig’s candidacy, but was probably influenced by the so-far political ineptness of Colin Craig. National may opt to support ACT’s David Seymour in Epsom and perhaps gain some MPs riding the coattails.

Mana’s proposal is partly indicative of the state of New Zealand political party culture. Due to the ghosts of FPP and for political convenience, it’s easy to expect more lobsters stuffed with tacos for the near future.

LABOUR IN VAIN OR THINK ‘BIG NORM’?

The Labour Party entered this election year in a better state than any year since the post-Helen period post-2008, but now struggles to gain consistent traction in opinion polls and has some left commentators already headed for the lifeboats. Part of this is due to with the popularity and political adeptness of John Key. Many argue it’s all David Cunliffe’s fault, same as Phil Goff and David Shearer before him. Yet, leadership is only part of the problem and at heart is more of a Labour problem. What prevents Labour from reaching it’s full potential so far is that it is still haunted by two ghosts: Roger Douglas and Helen Clark. Exorcising these ghosts will be decisive this year and beyond.

The ghost of Roger Douglas emanates from the economic reforms enacted by the Fourth Labour Government of 1984 to 1990. New Zealand was transformed from a protectionist welfare state to the deregulated free market state of today. As a consequence, Labour destroyed itself. The party membership decline from about 50,000 in 1980 to about 7,000 in 1990 and the split to Jim Anderton’s New Labour Party helped keep Labour from office until1999.

The ghost of Helen Clark is that her personality and style literally held the party together from 1993 to 2008 to the point it has not been able to move on. Helen reunited Labour through both public repudiation of the depth and speed of Rogernomics and the inclusion of Rogernomes such as Phil Goff and Annette King in high-ranking positions. This was solidified by her top-down management style that ensured unity.

Helen’s ascendency coincided with the global rise of the Third Way philosophy of modern social democracy: the acceptance of the key tenets of neoliberal economics. The worldwide centre left – most notably Tony Blair, Bill Clinton, Gerhard Schroeder, and Helen – espoused this as a compromise with neoliberalism. Yet, this approach broadly failed to address growing income inequality, cartel pricing of food and amenities, and support of global trade agreements that undermined national sovereignty and their natural blue collar support base. Without the discussion of economics and class from a left wing perspective, the centre-left globally was ill-equipped to address the looming Global Financial Crisis.

Helen’s top-down management style also enabled a party culture that hampered new ideas. In a previous post, I touched on my experiences as a Young Labour member attending national conference in Christchurch in 2003. Meeting Young Labour members, I was impressed with their dedication and politics further to the left than I expected. Yet as a group, especially from the executive, there was an emphasis on loyalty as more important than healthy debate. Political aspirations meant not pissing off important people. This made Labour bereft of new ideas.

After Helen’s retirement in 2008, Goff, Shearer, and so far Cunliffe have been unable to achieve unity. The 2011 party list rankings that entrenched incumbents and promoted lacklustre talent up the rankings was the result of the top down emphasis on loyalty. Under the leadership of Goff and King, both former Rogernomes, Labour developed a weak policy narrative that failed to address structural inequalities. Though flagship policies on capital gains tax, opposition to state asset sales, a higher minimum wage, and more apprenticeships were each smart, but didn’t address root causes of inequality, didn’t express a distinctly left wing narrative, nor outwardly made enough of a difference in peoples lives. Shearer and Cunliffe so far have introduced more of the same: NZ Power, Kiwi Assure, and the Sure Start Package. Technocratic and substantive, but not enough to speak to peoples needs.

Most critics blame leadership, but a real solution begins with a coherent alternative centre-left platform for the post-Global Financial Crisis age. So far, this has alluded the global centre-left for two reasons. Firstly, it has not developed an easy-to-understand left narrative of the GFC. Secondly, it hasn’t answered the failures of neoliberalism, especially the neoliberal ownership of the word ‘freedom’ – which really means exchange. Thirdly, the ghosts loom large. Like UK Labour with Blair and Brown and now Australian Labor under Kevin and Julia, NZ Labour needs an exorcism.

The last centre-left government in New Zealand who achieved both pragmatic, transformative change and balanced economic and social priorities was Norman Kirk’s Third Labour Government of 1972-1974 and Bill Rowling until 1975. Kirk and Rowling’s successes were based on a civic notion of what government could do well through policies that ordinary people could understand and feel. Within three years, they introduced reforms entrenched in NZ politics: ACC, the Domestic Purposes Benefit, the New Zealand Superannuantion Fund (repealed by Muldoon and revived as KiwiSaver), the Waitangi Tribunal, protested nuclear testing in French Polynesia, and cancelled a Springbok tour of New Zealand. These policies were vindicated by history and endure today.

Six months is a short timeframe to develop this vision, but perhaps Labour – through leadership, caucus, and the Policy Council – has already considered a different approach. Labour has already signaled changes to core neoliberal tenets such as corporate cartel pricing and Reserve Bank inflation policy, but this needs to be weaved into a larger, more passionate vision. One that cannot be as bureaucratic, protectionist, and top as before 1984, but one that understands modern concerns.

One part of that vision could emphasise Kirk’s approach of what government does best.

This means both a narrative of civic values and individual empowerment of individual opportunity – regionally and nationally – with community and individual as interdependent. Regionally, this could be as simple as the expansion or establishment of regional colleges, polytechs, and institutes to provide high quality degrees and diplomas specific to regional industries and employment pathways for graduates, and revitalise regions. Nationally, the expansion of faster passenger rail networks could be sold as a way to connect communities, relieve growth and housing pressure in big cities, and encourage growth in satellite towns and regions. This could be started with priority to Auckland to Hamilton, Tauranga, and Whangarei.

Youth employment opportunities could be similarly expressed as a national and local concern with both a national and local solution. A voluntary National Service akin to Americorps could recruit high school and university graduates as conservation workers, teachers aides, or nurses aides as a pathway to employment and education, assist frontline staff, and address skills shortages. If the National Government made an agreement with McDonalds to recruit the unemployed through WINZ, Labour could address national and local needs for the public good. It could be dollar for dollar employment experience in charities for new graduates for periods of six months.

Another part of this vision could be to update traditional left wing concerns to provide contemporary answers to neoliberalism and freedom.

Industrial relations policy can incorporate modern concerns. Focus on unpaid corporate internships; temp, contract, and subcontract labour rights, and encourage a more grassroots, democratic union movement. Class has not disappeared, more or less relocated to call centres, retail, hospitality, and casual employment. Start there.

Housing policies could take from Labour’s historic urban planning ideas and articulate a left wing vision of community. Invest in social housing and state housing with the principle of freedom of people should be able to live near where they work rather than be forced further out by high housing prices. Develop new urban planning models that favour good design, architecture, green space, and affordability. Surely Labour could address food prices through more suitable, local means. Perhaps legislation and local collaboration to establish consumer cooperatives and farmers markets for cheaper food prices.

Education could arguably be Labour’s best opportunity to articulate a new vision that would contrast heavily to the bureaucratic speak of Hekia Parata. Labour could emphasise community control of schools and real freedom of opportunity for all students. Funding control could be decentralised with greater parent and teacher roles in school management and a holistic approach to education, rather than remain dependent on ideologically-driven education models and bureaucratic accountability measures. Connect education to housing, nutrition, health, and parental and student employment opportunities.

Cunliffe can learn from Kirk in terms of policy and vision, but cannot copy Kirk’s personal style. Cunliffe will never be the working class man who left school early and built his own house. The public and media already sees Key as the closest thing. Instead, Cunliffe could take cues more from Helen. Helen remained publicly unpopular with the image of a cold, childless, opera-loving academic in excess tweed. Better leadership and success in the 1996 election debates helped Helen rehabilitate her from a possible third place finish to being a respected leader. People loved Helen because she was a good manager. Cunliffe has been talked of as a Helen protege and preferred successor and that is true insofar as he could cultivate the image of smartest person in the room and the policy wonk. Though the degree of her top down approach could be detrimental, he could take some cues from Helen to address key organisational concerns: entrenched incumbency and lack of renewal, poor communications operations and messaging, and Shane Jones. Either Jones’s contradiction of party policy has implicit backing or is uncontrolled, it’s looking like the latter and makes Cunliffe look weak.

The centre-left cannot move on without a coherent alternative, especially to the neoliberal concept of freedom and modern expression of what it means to be left that people can understand and feel. This is crucial to exorcising the ghosts of the past. Party disunity is partly indicative of a lack of vision. When Labour knows what it stands for and can articulate a people-centred vision, will it be in a position to challenge National.

ILLEGALS AND LANGUAGE OF THE BODY POLITIC

The use of language to create visual spectres is an effective approach for politicians, their supporters, and allied interest groups to develop a narrative that can become the media narrative.

A couple of weeks ago, I was reading a work report related to asylum seekers in Australia, and had noticed two significant changes made by the Australian Federal government to legal and bureaucratic terminology. First was a change to the term used for those who arrive by boat from ‘Irregular Maritime Arrival’ to ‘Illegal Maritime Arrival’. The aim of this was to legitimise PM Tony Abbott’s assertion of the illegality of arriving without a visa, which legally speaking isn’t true.

Second was the renaming of the ‘Department of Immigration and Citizenship’ – which oversees asylum seeker applications – to the ‘Department of Immigration and Border Protection’. This reinforces the shift from multiculturalism and legal process to gatekeeping, which began under Howard, revived by Gillard and Rudd, and now simply confirmed by Abbott. Even the costs of changes to departmental website, new logo, stationary and letterhead, updating of legal documents, and new business cards often proves expensive, but is trumped by politics, regardless of accuracy.

These changes institutionalise an image of asylum seekers as criminals deserving to be sent to the Pacific version of Devil’s Island. The irony of sending ‘criminals’ to a South Pacific prison colony seems lost on the Australian public.

Political convenience can also treat similar humanitarian cases differently. Consider the S.S Exodus, the people-smuggling boat run by the Jewish Haganah containing European Jewish refugees captured en route to Palestine by the British in 1947, which has become symbolic of a humanitarian cause. Comparatively the Hazara,the vast majority of Afghan people who arrive to Australia by boat and have experienced centuries of persecution and genocide up until today, have an equal case for humanitarian protection. But due to political reasons, public bigotry, and the need of politicians and media to gain an audience, the narrative suggests a “wave”, “swamp”, “flood”, “surge”, or other water-based metaphors coming to take our jobs and blonde virgin daughters.

Key to a successful narrative is a convincing visual spectre which we can project our own hopes and fears. The image of asylum seekers reflects a fear of the foreign other coming to dominate us. Locally, one of the most successful narratives is the fear of a large, interventionist state.

The most prominent concept is the ‘Nanny State’ – the use of state coercion to achieve results. The visual spectre reminds me of Hyacinth Bucket: telling you how to do things and being overbearing. This narrow definition only touches on perceived state intervention in personal choices rather than one that includes accumulated state powers such as spying and collection and storage of internet data. Instead this is limited to purchases, parenting, and dietary choices where freedom is treated similar to personal consumer choice and verging on paranoia. A “quick, hide the non-regulation lightbulbs or the state will collectivise our children” school of thought.

Another successful narrative, on the size of the state, uses language suggesting a large state as akin to a morbidly obese person. Less Nanny State, more ‘Fatty State’. When the public sector is deemed too large, it’s referred to as a ‘bloated bureaucracy‘, akin to an overweight person winched out of the house by crane. Solutions entail weight loss metaphors: ‘belt tightening’, “a leaner, more efficient state”, ‘trimming the fat’ through cutting backroom administrators and to free up or hire front line staff

If you assume the state was similar to an obese person, administration is the ‘fat’ and the front line staff the ‘muscle’. Weight loss requires healthier eating, exercise, and in some cases a stomach staple or liposuction. In reality, redundancies aren’t necessarily healthy choices. Redundancies often shifts admin to remaining staff, who work on tasks previously done by backroom staff. To cope, a government department may hire contract workers or temps at a higher price, albeit usually short term. Governments may subcontract state responsibilities to not-for-profits, not as partners as before but to carry out state functions, political agendas and admin for cheaper notable with the successor to NZ AID, the Sustainable Development Fund. Then there’s private consultants hired to advise redundancy processes, who are expensive and often have offered bad advice such as “pray, do yoga, and get a pet” – the equivalent of a dietary coach who suggests a lemon cleanse diet for a month. This part of the solution equivalent to wearing spanx: no ‘fat’ is really lost, more or less rearranged into more convenient areas.

Interestingly, right wing governments who use this approach also tend to favour more accountability measures for government spending which requires even more admin, often done by front line staff. With National Standards in primary school, teachers must spend more time measuring progress of every child against standards, which means more admin and teaching preparation. Metaphorically, fat can useful when exercise can transform it into muscle, but removing fat can hinder muscle performance and growth.

This metaphor undermines state functions with exactly what it promised to eliminate, like a bad diet and exercise plan. The linguistic metaphor works because of a body conscious society, in which our own fears over our weight are used to describe the state where even the littlest thing is unhealthy “pork”. In that sense, ACT and the Taxpayers Union claims of pork and waste are often the equivalent of the yelling of militant ‘fat camp’ coaches with a strict sense of outward discipline but with occasionally let slip.

Political language can be dangerous when used improperly. The narratives of the asylum seeker and the state trivialise rational debate and confine it to narrow ideas of legality, scope, and size based on prejudice and political convenience. In the case of asylum seekers, political agendas, media simplicity and public prejudice have institutionalised unhealthy realities. One person’s suffering is another person’s criminal punishment. The Nanny State concept is narrow and selectively misses the point about a broader encroachment of state power from all sides. The linguistic ideal of a state akin to a near zero body-fat All Black is a projection useful in a body-conscious society. The state could improve, sure, but isn’t obese. Both physical and metaphorical bodily ideals of perfection are deluded, unachievable, and unhealthy. Inclusive narratives with apt metaphors help, narrow ones are more likely to hurt people.